What It’s Like to Drive a Honda N-ONE e:, a Japan-Only K-Car EV

I recently had the opportunity to borrow a Honda N-ONE e: for five days. What makes this car particularly interesting for international readers is that it belongs to Japan’s unique kei-car (K-car) category, a vehicle class that exists only in Japan.

Kei cars are defined by strict size and engine regulations in case of ICE vehicles. They are compact, lightweight vehicles designed for efficiency and urban practicality. In exchange, owners benefit from lower taxes and insurance costs. The N-ONE e: is an electric version of this uniquely Japanese automotive concept.

Day 1: Long-Distance Driving in a K-car EV

Kei cars are often associated with short urban trips, narrow streets, and practical daily errands within neighborhoods. So I was curious: how would an electric kei car perform on an expressway?

With an estimated range of around 160 km displayed on the meter, my expectations were modest. Yet cruising at a steady 80 km/h on the expressway felt surprisingly relaxed. The silence typical of EVs, combined with adaptive cruise control, made the drive comfortable.

It challenged my preconception that a kei car is “only for the city.”

Still, the charging infrastructure revealed limitations. Rapid chargers in rural areas were sometimes difficult to access, and payment systems were not always intuitive. For wider EV adoption, especially among ordinary drivers, usability matters as much as battery capacity.

Day 2: From Inland Saitama to Yokohama

The next day, I drove from inland Saitama to Yokohama. On the second day, starting with roughly 219 km of indicated range, the drive was smooth even with expressway traffic.

For a vehicle that fits within Japan’s kei regulations, narrower and shorter than most global subcompacts, the N-ONE e: felt stable and confident. I finished the day with comfortable range remaining, reinforcing the idea that even a kei-class EV can handle medium-distance travel.

For readers outside Japan, this may be surprising. Vehicles this small are rare in North America, and in many countries such a car would be considered unusually tiny. Yet within Japan’s infrastructure and driving environment, it feels perfectly natural.

Day 3: A K-Car in the City

I briefly considered a longer drive toward Shizuoka Prefecture, but instead chose a shorter urban trip to photograph the N-ONE e: against Tokyo’s cityscape.

In fashionable districts like Aoyama, the compact kei-car silhouette stands in sharp contrast to luxury SUVs and imported sedans. In the 1980s, the Honda Today, a stylish kei car of its time, was even marketed as a product of Aoyama, carrying a certain urban sophistication. Against that historical backdrop, the design of the N-ONE feels overly modest, perhaps even too restrained for such a setting.

This was, admittedly, a slight disappointment. I found myself wishing that kei-car EVs would aim to be more visually compelling; not merely symbols of environmental consciousness or economic efficiency, but attractive objects of design in their own right.

A Broader Reflection

Driving the N-ONE e: reminded me that EV discussions are often dominated by large vehicles with long ranges and high price tags. But Japan’s kei-car ecosystem presents another model: small vehicles optimized for local realities.

The N-ONE e: may only be available in Japan, but it raises an interesting question for global mobility debates:

Do we always need bigger batteries and bigger cars, or could smaller, lighter vehicles meet most daily needs?

2026/02/16 8:10 PM - Tweet Facebook

Charging PHEVs/EVs in Japan

I drive a Honda Clarity PHEV, which runs on electricity for most of my short trips on ordinary roads. That means it needs to be charged regularly. I usually charge at home, but I sometimes use public chargers located in many places around Japan.

In Japan, there are two main charging standards. Almost all fast chargers use the CHAdeMO standard, although the output varies by charger. Recently, ultra-fast chargers of around 90kW have appeared in some locations. Tesla Superchargers are also available in Japan, but they are far less common than CHAdeMO chargers. Most slow chargers use 200V and typically deliver about 6kW.

Fast chargers are installed at most expressway service areas. You can also find them at Nissan and Mitsubishi dealerships (and increasingly at other manufacturers), public facilities, shopping malls such as AEON, and some convenience stores. Slow chargers are less common, but they are often installed where people park for several hours, such as shopping malls and public buildings. Their locations can be checked on websites like EVSmart and GoGoEV. There are, also, very few FREE fast chargers offered by municipality governments.

Although these chargers are operated by many different entities, their payment methods are somewhat standardized. Most belong to the eMP network and use a chip card for authentication and payment. To use them, you need an eMP-compatible card, which you obtain by subscribing to one of several services offered by different automakers, something that is quite confusing for users. Each automaker (such as Nissan) offers its own card to EV buyers through dealers, and you can also obtain a card directly from eMP. However, both the monthly fee and the per-use fee differ depending on the card you choose. For example, the table below compares several fee plans:

| Monthly fee | Fast charger | |

| eMP | JPY 4,180 | JPY 27.5/minute |

| Nissan (Premium 100) | JPY 4,400 | 100 minutes of free usage and JPY 44/minute thereafter |

| Nissan (Premium 400) | JPY 11,000 | 400 minutes of free usage and JPY 33/minute thereafter |

| Mercedes | JPY 5,720 | JPY 16.5/minutes |

Once you sign up, you must pay the monthly fee even if you never use a charger. For PHEV owners or drivers who rarely use fast chargers, this makes having a card feel like a waste of money. I don’t have a card for this reason. When I travel long distances, I usually fill the fuel tank and rely on the engine instead of electricity.

In the last few years, however, more chargers no longer require an eMP-compatible card. Independent networks such as ENEOS, EneChange, and Plago have been expanding. Premium Charging Alliance offers ultrafast chargers with astounding 150kW capacity. Although they offer subscription plans, you can also use their chargers without subscribing. Typically, you install an app, register your credit card, and then pay per use with no monthly fee. eMP has now adopted a similar scheme. I haven’t tried it yet, but apparently you scan a QR code on the charger, enter your credit card details each time—which sounds rather clumsy—and then the charger operates at a steep rate of 77 JPY per minute for outputs of 50 kW and above.

AEON malls used to offer very affordable charging without a membership fee (though you needed a WAON IC card, which you could also use for shopping in the mall). Now they are part of the ENEOS network, and the fees are the same as other ENEOS chargers.

One nice thing about charging at AEON malls is that you can usually find a parking space even when the mall is very crowded on weekends. I sometimes charge at AEON malls simply because their charging spots are more likely to be available.

2026/01/16 4:26 PM - Tweet Facebook

Renewing driver’s license in Japan, Saitama style

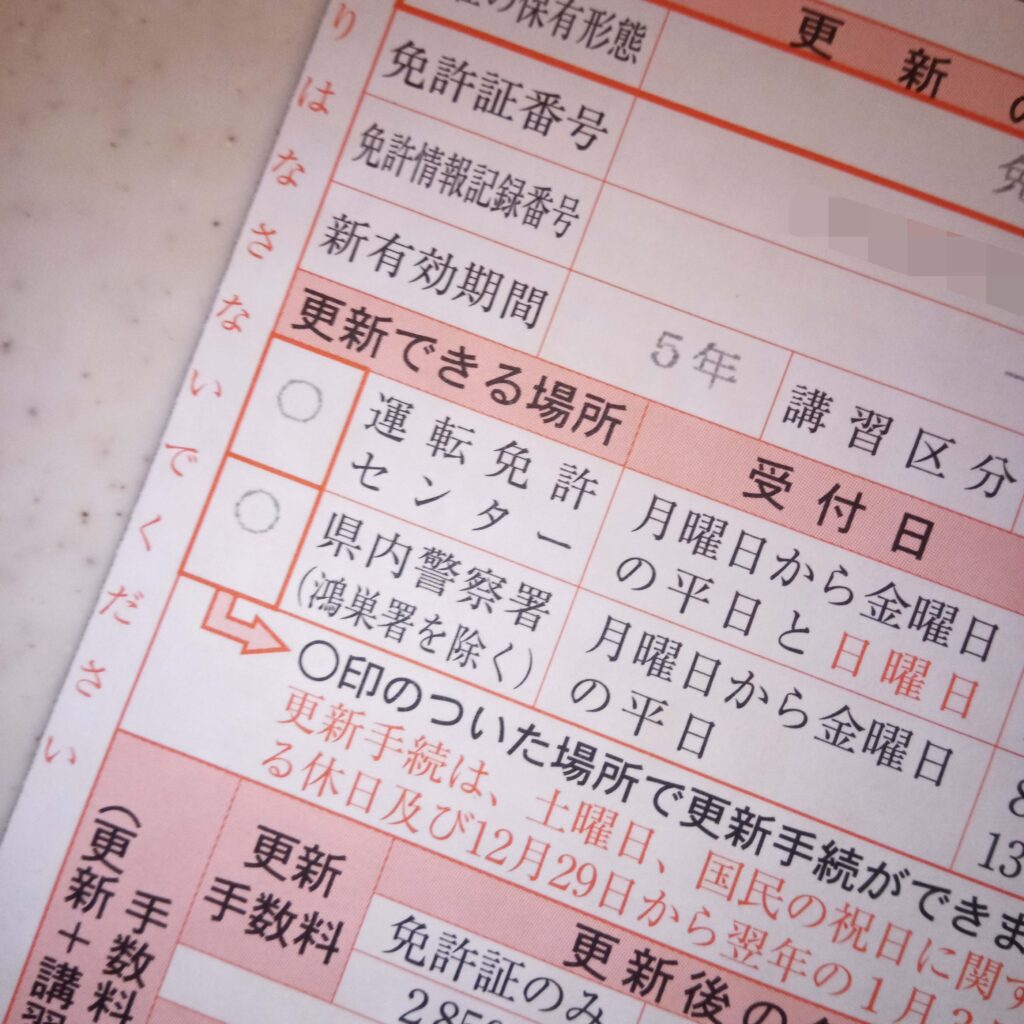

In Japan, a driver’s license is usually valid for five years. That means, every five years, we have to go through the renewal process, with the deadline set on the license holder’s fifth birthday.

A few days ago, I received the renewal notice from Saitama Prefectural Police.

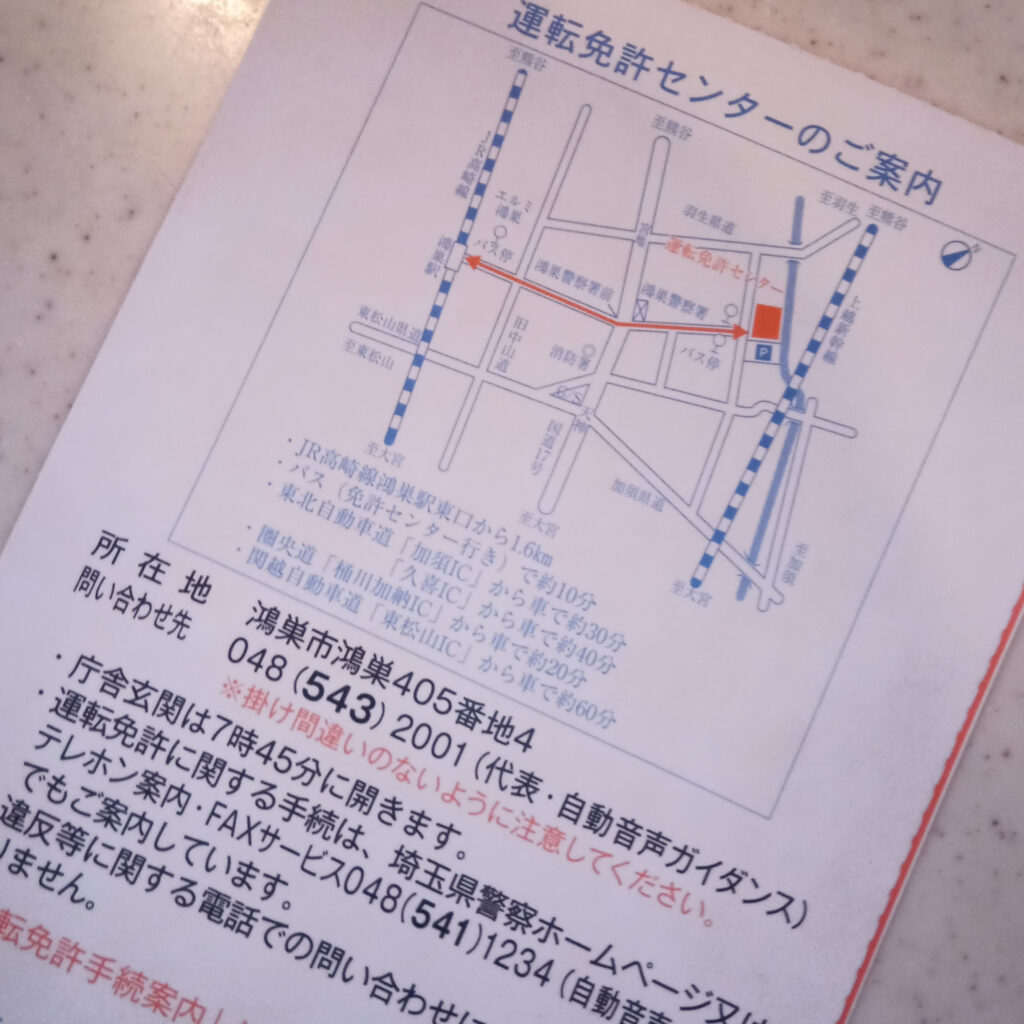

When I flipped the postcard over and saw the map on the back, I felt a small jolt of fear. According to it, I might have to go all the way to the main “licensing center” in Kōnosu City, in Saitama Prefecture.

Typically, each prefecture has only one such “licensing center.” If you live far from it, that can easily mean an hour or more of travel each way just to renew your license. Kōnosu sits more or less in the geographic center of Saitama, but for those of us living in the southern part of the prefecture, it feels quite far away. Since most people in Saitama live in the south, largely because of its proximity to central Tokyo, going to Kōnosu inevitably turns into a bit of a journey.

It’s pretty unreasonable. But at the same time, it may also function as a kind of “soft law”: behave yourself for five years and you’re rewarded with the convenience of renewing your license at a nearby police station. Get caught committing an infraction, and you’re sent to the distant central facility.

I was fairly sure I hadn’t been caught doing anything over the past five years… so I opened the postcard, slightly nervously…

…and discovered that I can renew my license at my local station. Relief.

These days, it’s also possible to merge your driver’s license with Japan’s My Number (“Myna”) card. In theory, that sounds modern and convenient. In practice, though, the benefits seem minimal. The fee is a bit cheaper, but the process takes longer than simply having a conventional license card printed. Which basically means spending extra time sitting around at a police station, not exactly everyone’s idea of efficiency.

Anyway, I’m glad I don’t have to make the long trip to Kōnosu, more than an hour away from home. Still, part of me thinks that a day trip to the northern part of the prefecture might not have been so bad… a bowl of local udon noodle, a change of scenery, and a short break from the usual busy routine.

2026/01/10 9:39 PM - Tweet Facebook

Japan-made electric buses in a world that has already moved on

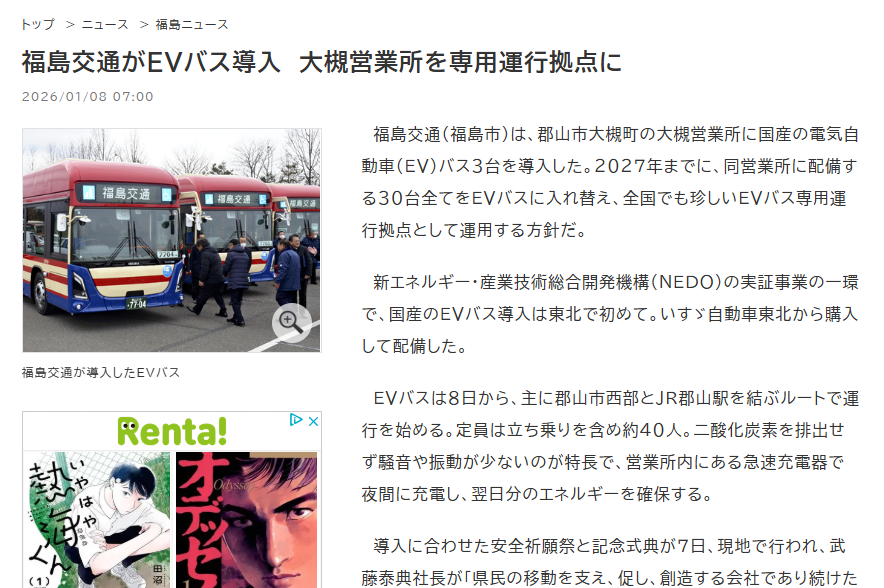

A local bus company in Fukushima Prefecture has begun introducing 30 electric buses as part of an “experimental” project subsidized by the national government. According to a news report, three of the vehicles are already in operation.

福島交通がEVバス導入 大槻営業所を専用運行拠点に:福島ニュース:福島民友新聞社

One point the article seems to emphasize is that these buses are “made in Japan” (kokusan).

This emphasis is understandable. Last year, several China-made electric buses caused a number of problems, particularly around the Osaka Expo site, and they gained a somewhat notorious reputation as a result. In that context, the “made in Japan” label may help ease passengers’ concerns.

The buses appear to be Isuzu’s Erga EV.

Based on information available on the manufacturer’s website, the vehicle has a stated range of about 360 km, though this figure assumes a constant speed of 30 km/h, which is not exactly realistic for daily urban operations. In terms of size and exterior design, the bus looks fairly conventional. Charging is supported via a plug-in connector with a maximum output of 50 kW.

When compared with electric buses already in service in other cities, particularly in Europe, this does not feel especially impressive. Many European systems have moved toward faster and more flexible charging solutions. According to the Fukushima report, these buses need to be charged overnight to cover a day’s operation. In practical terms, that likely limits each vehicle to well under 300 km per day.

To be clear, I am not arguing that China-made buses are better. Still, it is a bit disappointing to see that Japanese-made electric buses do not stand out more in terms of technological ambition or innovation. Another experiment reported in Kawasaki is expected to introduce pantograph-based super-charging systems, but even those have already been deployed at scale in other countries.

I sincerely hope that Japanese bus manufacturers will take a further step: one that truly surprises the world, rather than merely catching up with what has already become standard elsewhere.

2026/01/08 9:24 AM - Tweet Facebook