June 24, 2025

Climate assemblies meet transition management: experimental applications in Japan

Below is the abstract for my presentation at the International Sustainability Transition 2025 Conference (June 24-26, Lisbon, Portugal):

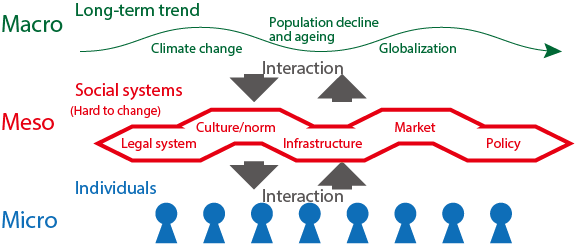

Climate assemblies have emerged as a key mechanism for public participation in climate policymaking. National governments and municipalities, particularly in Europe, have increasingly adopted this deliberative model to incorporate citizen voices into climate strategies (Elstub et al., 2021). These assemblies convene randomly selected citizens to discuss and propose recommendations for climate action. While they represent a step toward participatory governance, they often overlook how to engage citizens in broader socio-technical transitions. Climate policy requires not only policy shifts but also changes in public attitudes and behaviors. Strategies that facilitate such shifts are crucial for ensuring that climate assemblies contribute meaningfully to sustainability transitions.

Despite the importance of transition-oriented approaches, strategies rooted in “transition management” (TM) have been largely absent from climate assemblies. Transition management, as conceptualized by Loorbach (2010), provides a governance framework that steers societal transitions through participatory and reflexive processes. One of its key tools, the X-curve, visualizes phases of decline and emergence in socio-technical systems (Loorbach et al., 2017). Although widely applied in sustainability governance, TM has not been systematically incorporated into climate assemblies, presenting an opportunity for experimentation and innovation.

In response, an experimental application of TM was undertaken in municipal climate assemblies in Matsudo and Setagaya, Japan. These initiatives represent one of the first known efforts to integrate TM principles into climate assemblies. This study explores the motives, implementation, and outcomes of these experiments, drawing on the author’s direct involvement. The objectives were: (1) to assess whether TM tools could enhance citizen deliberation on long-term climate strategies, (2) to examine their impact on the outputs generated, and (3) to evaluate whether they foster more profound engagement with transformative climate governance.

Transition management elements were embedded in the assemblies as part of a half-day-long session on transition thinking. The X-curve was introduced to help participants conceptualize societal shifts needed for climate action. Instead of focusing solely on current policy gaps, participants envisioned declining and emerging elements of a sustainable future. Participants were asked to deliberate on the kinds of transition strategies, including identifying existing niches in their townships and exploring the ways of scaling them up.

The integration of TM yielded several insights. The X-curve provided a structured yet flexible framework for participants to navigate the complexity of climate transitions. Discussions moved beyond policy recommendations to consider systemic change, trade-offs with incumbents, and long-term feasibility. Additionally, incorporating behavioral and attitudinal change discussions increased participants’ sense of agency in shaping climate futures beyond government actions. The iterative TM approach also led to more nuanced recommendations as participants refined their proposals in response to evolving discussions.

However, challenges emerged. One difficulty was the absence of frontrunners among the participants. They were randomly selected citizens in order to form the arena as “mini-publics.” Thus, the guiding principle of TM, which selectively invites future-oriented innovators to its transition arena, was somewhat incongruent with the setup of climate assemblies. Also, ensuring that TM-integrated assemblies effectively influence policymaking remains an ongoing challenge. While being enthusiastic about emerging practices, these randomly selected participants were reluctant to depict the incumbents with negative connotations.

Overall, the experimental application of transition management in Matsudo and Setagaya suggests that transition-oriented tools can enrich deliberative processes and enhance citizen engagement in climate governance. Findings indicate that a more explicit TM perspective in climate assemblies can help shape societal transitions toward sustainability. As climate assemblies evolve, embedding transition-oriented strategies may provide a crucial mechanism for fostering more profound and transformative engagement in climate action.

References:

– Elstub, S., Carrick, J., Farrell, D. M., & Mockler, P. (2021). “The scope of climate assemblies: lessons from the Climate Assembly UK,” Sustainability, 13(20), 11272.

– Loorbach, D. (2010). “Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework,” Governance, 23(1), 161-183.

– Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). “Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599-626.